With Mute Assent

August 15, 2014

There’s are good and prudent reasons not to have armies policing citizens; they have to do with issues of function and mental attitude. A police force is established to protect citizens against lawbreakers, armies are created to fight wars. It’s all about training and mindset. A police force with a military state of mind will find an enemy because, like nature itself, we and our armies abhor vacuums.

Of the many human inclinations, we (especially of western civilization) are creatures of accumulation. We cram empty spaces with stuff —our houses brim and overflow into landfills; we stuff empty minds with stuff —jam them with useless info while discarding wisdom to make room; we forever invent new stuff and always find new reasons to use it.

We invented the wheel and rolled over everything. We invented the light bulb and lit up the world. We invented vaccination and decimated disease. We invented the atom bomb and gave it an immediate tandem tryout in Japan to demonstrate it worked. We invented guns and (fulfilling the fiscal dreams of the NRA) the world became a collection of armed camps looking for a fight. And now, as the federal government unloads new and surplus military paraphernalia —guns, helmets, grenade launchers, armored personnel carriers, flak jackets, camo suits, boots— on local police forces, an ill wind smelling of teargas and gun power, is filling vacuums of our own making.

Almost inevitably, as a poem says:

cops with army stuff

use more army stuff,

find more reasonswith more reasons

sometimes killtasers, small tanks, flack vests

big muscle guns, jackbootstoughen up

with army stuffturn up heat

see if gizmos work

go boom rattatat

zap hurt

The most recent vacuum into which our growing domestic army has been sucked is called Ferguson Missouri, a town in which a war-equipped police force took to the streets to compel both outraged citizens and an inconvenient media to shut up.. Citizens were outraged because another unarmed man, young and not coincidentally black, was gunned down in the street in broad daylight. But no one had to call the police because the police were already on the scene. In fact, the police did it.

The camouflaged Ferguson troops (who could nevertheless clearly be seen) geared up for the apocalypse with heavy armament, in Kevlar vests emblazoned “POLICE”, backed up with tank-like vehicles, faced off with an enemy armed only with signs and shouted exclamations such as: “Don’t shoot me!” Most of that enemy happened to be black because, incident after recent incident, unarmed young black men have been shot and killed by vigilantes and police: Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, John Crawford, Ezell Ford and now, Ferguson’s Michael Brown. It should come as no surprise that things finally reached critical mass in at least one black community. Call Ferguson a tipping point.

What’s happening? What’s happening is that our vaunted system, based upon the equal application of law, is being outed as one that is just not. Journalist Glenn Greenwald in his book, Liberty and Justice for Some, lays out the reality that has eclipsed an ideal never realized:

“From the nation’s beginnings, the law was to be the great equalizer in American life, the guarantor of a common set of rules for all. But over the past four decades, the principle of equality before the law has been effectively abolished. Instead, a two-tiered system of justice ensures that the country’s political and financial class is virtually immune from prosecution, licensed to act without restraint, while the politically powerless are imprisoned with greater ease and in greater numbers than in any other country in the world.”

Greenwald does not exaggerate. Our prison population stands now at more than 2.4 million or about 8% of the population —the highest in the world. 40% of these are black, although blacks are only just under 14% of the population. Anyone with an open mind who pays attention to the news knows this has more to do with the way justice is meted out in the US than it does with the inherent character of people of color.

In the aftermath of the economic collapse of 2008 virtually none of the crooks responsible: politicians, shyster bank executives, junk bond marketers, or CEOs of any failed (or too-big-to-fail) financial institution has seen the inside of a jail cell, but anyone stealing a loaf of bread from a convenience store has probably found their way there. Our legal system protects the rich and powerful and their police forces behind heaps of Benjamines stacked higher than the walls of the Department of Justice. In fact, justice is not served it’s dished out to each according to his financial means.

Looking at Ferguson, Missouri —it’s massed police, its clouds of tear gas, is guns, it’s combat gear, its blue-uniformed gun-men, its official belligerence, its killing of unarmed men — is not something that conjures up the American dream. Instead it conjures a glimpse of an American future that signals that the dream and its tortured democracy is dying before our eyes, with our mute ascent.

Jim Culleny

8/21/14

.

Same as it Ever Was

August 1, 2014

I read an essay recently by John Michael Greer in his blog, The Archdruid Report. It ends with this:

I read an essay recently by John Michael Greer in his blog, The Archdruid Report. It ends with this:

“(now) I’ll … return to the ordinary business of chronicling the decline and fall of industrial civilization.”

Ominously, the essay ends there after Greer has run through what he suggests are three effective ways to deal with the”…the decidedly mixed bag that human existence hands us.” The Greeks, he says, tackled this mixed bag head-on in three of their schools of philosophy: Epicurean, Stoic and Platonic.

According to Greer, students of the philosopher Epicurus, Epicureans, start with the premise that life is better than death. Most of us would agree (some more grudgingly than others) while many —those who find their backs chronically against the wall— concur most heroically and press on with life anyway. But there are those who have an absolutist, otherworldly bent and simply do not value earthly lives, their own or others, so highly—suicide bombers, for instance, or fundamentalists longing for the “end days” and Armageddon. Epicureans do not long for end days and, by and large, most of the rest of us if given the option prefer to stay alive with as little TV-style blood-letting as possible.

The Epicureans of Greek philosophy focus on the pleasures life offers (but, as is typical in Greek philosophy, with moderation). This is expressed, Greer says, in the “…calm realism you…often seen in people who’ve been through hard times and come out the other side in one piece.” We in the contemporary First World, unlike people wrung dry in the great depression, find this view hard to adopt because we’ve been through “…an age of extravagance and excess.” We expect pleasure to be almost infinite. To help comprehend this, think wall-sized TVs with ultra-bass surround-sound, cars that parallel park on their own and landfills of waste the size of tiny Himalayas that dot our landscape: pleasure without moderation.

Another Greek view, which comes at life’s dark side from another angle, is called Stoic. Stoics realize that, good or bad, whatever happens, we’re here now so what are we going to do about it? We each must choose a response. Stoicism is an approach that recognizes the value of change and action (often at the risk of life) to rectify those aspects of life that are unjust, dangerous, absurd, etc. —not because this life has no value, but because it does and the risks involved in change are worth it, not only for ourselves but for others.

Digging heels in against change would not be the Stoic’s way according to Greer. By this standard, there are probably few Stoics in the Tea-Party, the US House of Representatives, on Wall Street, in extreme religious sects, or among white supremacists where progress is often anathema. Among these groups change is seen as a cramping of decadent me-first life-styles, an assault upon the word of God or a slap in the face of belief in traditional racial or male superiority.

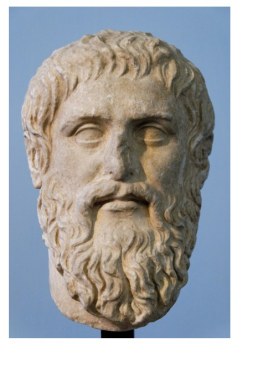

Finally, Greer gives us the Platonists. Plato imagined something beyond perception: a reality behind the perceived, a view which shares something of the magical thinking we find in religion and politics today. Aristocles, nicknamed Plato, taught that this reality is independent of human whim and wish.

Star-gazing astrophysicist, Sir Arthur Eddington, may have been loosely channeling Plato when he said, “Something unknown is doing we don’t know what,” which is suggestive of what Chinese poet Lao Tzu wrote twenty-six centuries earlier: “Heaven conforms to the Way (Tao). The Tao conforms to its own nature.”

I’m not a Platonist in a magical thinking sense, but may be in a scientific one, which is to say, if scientific method hypothesizes an invisible reality (such as “dark matter”) I’m more inclined to accept it than if it’s a claim of “revealed” truth. Why? Because science, in an attempt to understand that which changes (which is everything we experience), follows a rigorous experimental method designed to get past static “revelation”. The difference between this and a religious approach is that when science hits the wall it says, we don’t know but will continue trying. I like science’s structural humility.

Scientists, when they hit the wall of the unknown, are, like all of us, left only with something like astrophysicist, Eddington’s “something unknown is…” remark. Being a curious species, it’s frustrating not to know; and being a species which names, we must name it: God, Tao, The Unknown or Something.

In our time philosophies and religions are at war. Maybe, as the Talking Heads sang, this is “the same as it ever was”. However, the singular difference is that the stakes are much more profound because our technology is magnificently more powerful and our willful ignorance more catastrophic.

When we have Senators and congressmen who assume the attitudes of priests and shamans while enjoying fortunes built by scientific method we have the symptoms of societal schizophrenia with all of schizophrenia’s delusions writ large. When we ignore the harm we’re doing to the planet and each other for the sake of our religious or ideological beliefs, dismissing the damage with ironically hopeful visions of a biblical apocalypse, we make more certain that we’ll have one —which may or may not be the same as it ever was but is profoundly more unacceptable.

.

Jim Culleny

8/1/14